CHAPTER 11: The Logging Scene

“Are we there yet?” Grace asked, wishing she’d skipped the third cup of coffee at breakfast. She urgently needed to end the vibration of the truck on the logging road.

“Almost,” said Jackson, oblivious to her distress.

“Seriously, Jackson, I need you to pull over. Personal reasons.”

He pulled the truck to the shoulder, reached across the cab and opened the glove compartment. Grace spotted a handgun behind the plastic bag of toilet paper and wipes Jackson handed her. “The essentials,” he said avoiding her eyes.

Grace hiked down a bank to the privacy of the brush, took care of business and climbed back up. Jackson was zipping up after watering a tree trunk.

“We’re only a few miles away,” he said as they settled back into the F-350. Willie Nelson and his son Lukas sang on the CD.

Yes, I understand that every life must end, aw-huh / As we sit alone, I know someday we must go, aw-huh

Oh I'm a lucky man, to count on both hands / The ones I love / Some folks just have one / Yeah, others, they've got none, aw-huh

Stay with me / Let's just breathe

Grace studied the trees out the window as the truck tackled the steep gravel switchbacks. Willie and Lukas sang on.

Practiced are my sins / Never gonna let me win, aw-huh / Under everything, just another human being, aw-huh

Yeah, I don't wanna hurt her, there's so much in this world / To make me believe

Stay with me / You're all I see

They topped a ridge and parked. Jackson left his door open, let Willie and Lukas finish their song while he got out and admired the view.

Did I say that I need you? / Did I say that I want you? / Oh, if I didn't I'm a fool you see / No one knows this more than me / And I come clean

A patchwork of trees along the timberline grew to thick and verdant on the lower slopes down to the valley. Above, mountain ridges stacked one behind the other to the horizon in ever-deepening shades of green streaked with gray and charcoal waves of the dead and dying.

I wonder everyday / As I look upon your face, aw-huh / Everything you gave / And nothing you would take, aw-huh

Nothing you would take / Everything you gave

Did I say that I need you? / Oh, did I say that I want you? / Or if I didn't I'm a fool you see / No one knows this more than me / As I come clean, ah

Nothing you would take / Everything you gave / Love you till I die / Meet you on the other side

Uphill, a man of 50 with a military haircut and a wide jaw leaned against his truck, drinking coffee from a thermos, patiently waiting. “Hey, Jack,” he said when Jackson and Grace joined him.

“Hey, Nate,” said Jackson. “Nate Halpirn, crew boss. Grace Newman, L.A. reporter.”

“That’s a journey,” said Nate, tipping his cowboy hat and shaking her hand. “Pretty dry down there. Never rains?”

“Not much,” she said. “But comes down hard every decade or so.”

He pursed his lips, shook his head. “Must be tough on the trees,” he said.

Grace nodded. “Must be,” she said, “but different trees down in SoCal.”

“Looking good up there,” said Jackson, surveying the logging scene on the side of a mountain opposite.

“Under control,” said Nate.

“Appreciate you walking Grace through it while I head over.”

“Can do,” said Nate.

Nate and Grace watched Jackson’s truck disappear behind trees.

“So,” said Nate, “today’s job is yarding logs uphill. This cut is on Armstrong land, next to fed land—overstocked, as usual.”

“Overstocked?” asked Grace.

“Plenty of seeds buried in these soils. Add a little sun, some water and away they go. Natural regeneration. DC bureaucrats decided to speed that process up with regs requiring tree planting after harvest. Regs require they be ‘free to grow’ without competition.”

“You disagree with this?”

“I do,” said Nate. “Takes us further from forestry, closer to plantations. There’s a mycorrhizal network of fungi underground, connecting all these trees. Seedlings that naturally regenerate rely on these fungi connections. Transplanted nursery-grown seedlings are not native to this forest and don’t connect to the site-specific fungi so every time I hear a logging company boast about planting six or ten trees or whatever for every one harvested, I cringe. Jobs program for PhDs, itinerant workers, students seeking school credits. Voters. All sounds good on paper—don’t always work in reality.”

“Hmmm,” said Grace. “So you’re looking for what? A balance between overstocked and a clear cut?”

“Yep,” said Nate. “Especially along the edges of the openings, there is far more biological diversity in early succession forests than in old forests. Stocking regs combined with fire suppression means many US timberlands are planted far beyond the land’s carrying capacity, all sucking up way too much water and blocking out the sun, killing everything below. No berries for bears there.”

Nate reached into the bed of his pickup truck and pulled out two books, handed her one, Forest Stand Dynamics by Chadwick Oliver and Bruce Larson.

“Homework,” he said. “This book outlines ways to disturb forest regimes through management to yield lumber or recreational values or forest structure diversity for improving biodiversity, whatever you want. ‘Adaptive management’ it’s called. It’s in play all over the planet.”

“Thanks,” said Grace. “I’ve read about adaptive management for biodiversity gains, habitat work.”

“Beyond that, forest watersheds create 75% of the planet’s fresh water so mismanagement of forests equals mismanagement of watersheds. Stupid rules are killing forests and downstream water flows.” He handed Grace the second book, Bruce Vincent’s Against the Odds: A Path Forward for Rural America, and said, “Bruce’s a logger, livin’ and workin’ smack dab in the middle of the Grizzly Bear Habitat Improvement Research Project out in Montana. Here, read this passage,” he said, opening a page marked with a paperclip.

In many areas, forests today have now become so thick that floor and invigorate an abundance of life forms is cut off. The grasses and berries that could, and should, have grown in the forested areas are far less abundant than before the canopy closure. As a result, creatures such as the grizzly bear, who rely upon the forest floor for sustenance, are slowly being choked out of their homes.

Worse yet, however, is the fact that trees are water pumps. A full-sized pine tree can suck two or three hundred gallons of water per day out of the aquifer and transpire it into the air. This transpiration is what gives forest areas the feeling of being ‘cool.’ Yet when there are too many trees fighting for a finite quantity of water, the trees become weak. The stressed trees emit a pheromone that is a sure signal to naturally-occurring bugs like the northern pine beetle that the tree is prime for attack. A healthy tree will be able to fight off a bug attack by exuding copious amounts of sap into the holes drilled into the bark by the bug intruder (this is where the term ‘pitch’ comes from since healthy trees literally ‘pitch’ the bugs out.) A weakened tree cannot win the battle with the bug and is killed. When entire forests are overstocked with too many ‘water pumps,’ they are prime targets for massive insect infestations. Such an infestation has been decimating the forests of the Rocky Mountains for several decades.

As alluded to earlier, Native American populations managed the forests with controlled, periodic burns for millennia. Now, with the removal of Native American management, trees that had for eons been killed when they were two feet tall in intermittent fires are now free to grow. And grow they have.

Nate opened the tailgate and rolled over a round cross section of a tree. “We call these cookies,” he said. “This slice is from a Doug fir born in 1546 on the South Fork of the Santiam River in Oregon. It was felled as part of a clearcut on the Willamette National Forest in the 1970s or ’80s, at just over 400 years old.” He read from a piece of paper, “Exact location: 44.298061, -122.330285.”

He patted the dark wood at the core. “Heartwood,” he said. “Old layers of sapwood and dead cells.” He ran his fingers along the rings in the lighter areas. “Sapwood,” he said. “These are the living cells containing water and the nutrient system of the tree. In both the heartwood and sapwood, rings reflect growth cycles. In simplest terms, fall and winter growth is reflected in the thin rings, spring and summer growth in the wide rings. When growth is strong—during periods of sun and moisture, it is reflected in wide rings. The narrow rings reflect periods of scant growth—fall and winter, during droughts and periods of cloud cover created by volcanic activity.”

He ran his forefinger over a charcoal fire scar. “Sometime between August and October in the year 1659, when this tree was 113 years old, fire left its mark. That disturbance was etched into the entire stand, present in every board cut.”

He looked out across the mountain and said, “Armstrong land is good land, managed land but sits next to fed land, overstocked, far too much fuel there. Just a matter of time before it burns way too hot. So we’ll take some of these trees before that happens, make a living from ’em. We’ll finish with a light burn—a prescribed burn—start a new forest on its way.”

Nate’s radio crackled. “Here,” said Nate, pointing to another page marked with a paper clip in Bruce Vincent’s book. “Read this while I take that,” he said.

Grace sat on the tailgate and read a passage.

…What would a natural forest look like without the heavy hand of utilitarian management by fire employed by the Native Americans? Certainly there would still have been natural fires introduced each year through lightning ignitions. But the question of what ‘natural’ fire regimes would look like, without any human influence, is simply not known. Nor do we know exactly what the forest would look like today if European settlers had never set foot in the landscape.

We do know that the fires of 1889 were large and burned a great deal of the landscape in one particularly rough season. We also know that the snags left behind during those fires suffered root loss, fell to the forest floor and provided the setting for the conflagration of 1910. The fire of 1910 occurred some 80 years after the removal of Native American management and was a result of some 80 years of ‘fuel’ accumulation in the Inland Northwest. It was, as we saw, a summer noted for its heat and a lack of rain that culminated in a fire-storm of epic proportions. The fires were so large that the people of Montreal Canada called 1910 the ‘Summer Without A Sun’ because our orb of life turned dark orange from the plumes of smoke circling the globe and stayed orange until the snows of winter cleared the air. Nature was cleaning up a mess in the forest.

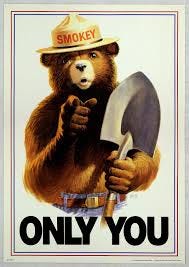

The fires of 1910 happened just four short years after the federal government, under President Teddy Roosevelt, had formed the United States Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management and set aside undeveloped lands to be managed for the public’s interest within the federal forest reserve. The move was made in an effort to protect the forests from overharvesting and to assure that they would be around for all future generations of Americans. When the public realized the extent of the damage caused by the largest fire in recorded history, they were incensed. The pressure was on to ‘save the forests’ from fires. Smokey the Bear became a mainstay that symbolized the public’s desire to keep the forests from burning to the ground. The forest managing agencies became extremely efficient in putting fires out.

…Forest scientists have long told us, however, that there is a downside to this efficient removal of fire from the forest ecosystems. The forest surrounding Libby and hundreds of communities in the west no longer have a ‘good’ fuel load. Around Libby, forests no longer have 50 or 60 trees to the acre. Across tens of thousands of acres, the average can be as many as 500 trees, and the trees are stressed. Many have been attacked and killed by beetles and other diseases. For the first time since forest inventories have been studied, the mortality in our national forests of the northern Rockies is outstripping the growth of the forest. It is the hope of those in our area that corrective forest restoration can happen before the three-million-acre 1910 fire is recreated. We know that time is not on our side concerning this eventuality, as the forest that grew out of those two days of hell are largely nature’s cover crop of lodge pole pine and ‘old’ for this species is around 100 years. This time the coming fires could be even worse, though, since we have another century of unimpeded forest growth under our belt and stacked in the forest. The fuel loads are tremendous.

…Today, not only is our population much greater, but we have very, very few rail systems in place and though we have highways that serve the area, our roads zig-zag through heavily timbered areas and are not where you want to be during a fire-storm.

Nate returned and pointed to the mountainside where Jackson was looking downhill, studying the work site. “OK,” he said. “Quick course in loggin’. Most loggin’ on the Olympic is done with towers,” he said. “We’re using a reconditioned Madill rig here today. Madill, Washington Iron, Thunderbird, all gone now, but used machines and parts are abundant.”

“Where’d those companies go?” asked Grace.

He scowled. “Out of business. Consolidation,” he said, almost spitting the word. “I hear the Californication of agriculture is pretty much complete down your way, right? Shame.”

He pointed to the tower. “Three large drums on that Madill hold cable the same way a fishing reel holds line. This tower, or tube, is 100 feet tall with a mile of haulback line—lets that monster yard logs as distant as a mile away.”

Grace followed Nate’s index finger downhill. “The tower operator sends cable down to the logging site and, in the reverse, the yarder crew retrieves the felled logs. Cutters—fellers and buckers—hand-felled and bucked these trees two weeks ago—mostly Doug fir, some cedar, a little hemlock. On the Olympic, felling and bucking is done with chainsaws. For the biggest trees, you’d be looking at a 48-inch bar chainsaw, generally Stihl brand. The fellers carry their own chains, gas, oil, wedges and axes with ’em. They lay the logs down side by side—directional felling—nice and neat, big ones on top of the smaller ones so they won’t shatter when they hit the ground. Makes yardin’ easier. No pickup sticks here. Once on the ground, buckers delimbed the trees, bucked 'em into sections, 32 feet on this job.”

He pointed downhill. “Watch ’em,” he said. Nimble as mountain goats, the men ran across the already-bucked tree trunks, secured cables around the logs.

Nate pointed and said, “Main line has a carriage. These are Eagle Skycars out of LaGrande, Oregon. Good company.

“There,” he said. “Cables—what we call chokers—are attached to the skycar that moves to where choker setters attach chokers to one or more logs, depending on weight. The whistle punk toots, signals the tower operator, the yarder operator, who can't see down in the hole where logs are choked. Toots mean different things, depending on what's happening down the mountain.” He listened for a minute. “There he said, that toot means logs are ready to be hauled up the mountain to the log landing. The cables affixed to the skycar enable it to haul multiple logs, depending on weight, to the tower on the landing.”

In his cab up the mountain, the yarder engineer blew his whistle, moved levers controlling big winches on cables attached to the tower, the skyline array. Logs flew through the air to the landing area next to the yarding tower.

Nate pointed. “Landing chasers work beneath the tower, removing chokers, use a chainsaw to bump, remove, knots and any remaining limbs from each log. Boom operators sort logs by size and species and they’re decked—we usually have two to three good sized decks for selecting logs—ready for loadin’ on trucks. We’ll debark at the mill where we have a real nice ring debarker.”

“I saw it,” said Grace.

“After the landing chasers finish with a log, the shovel operator, loader operator, picks it up, sorts and decks it by size or species and loads the trucks. Loading’s done by a heel boom. It picks up individual logs and lays them on the truck bunk. A good loader operator is worth their weight in gold ’cuz it’s vital the load be well balanced as to weight and log size.”

Nate pointed out a truck filled with logs. “It’s the log truck driver's job to put three to four wrappers around the load.”

“Wrappers?” she asked.

“Cables thrown over the top,” he said, “tightened with a steel bar under the load. Then we’re ready to head for the mill.”

They watched a log truck driver signal he was up to weight, strap the load down with log binders then zigzag down the mountain to the mill. An empty truck moved up, turned around, and parked. The process would repeat all day.

Nate’s radio crackled. As he moved away to take the call, he handed Grace his binoculars. She scanned the mountain, studied the men working. Streams of sweat trickled like muddy rivers down their faces.

Nate walked in her direction and Grace heard Jackson’s voice on the radio. “Selected a tree on the east face, 40% grade. Not sure it’ll hold a skyline. Take a look?”

“Can do,” said Nate. “Out.”

Nate turned to Grace. “Gotta go. There’s a nice spot,” he said, pointing to the base of a 200-foot Doug fir. “Grace, meet Doug. Doug, meet Grace.” He laughed and handed her a metal thermos of coffee and a small waterproofed canvas tarp. “Wet ground,” he said and left, drove away.

Grace laid the tarp under the tree, sat with her back against it, ran her hand over its rough, weathered trunk. “Hey, Doug,” she whispered.

A vista of green gently swayed in a mild breeze next to the rubble of the cut. To Grace, the logged area was emotionally wrenching, but she loved the scent of freshly cut fir.

Grace flipped open Forest Stand Dynamics, scrolled through the Preface and Index to Chapter 1, Introduction.

Forest stand dynamics is the study of changes in forest stand structure with time, including stand behavior during and after disturbances. A stand is a spatially continuous group of trees and associated vegetation having similar structures and growing under similar soil and climatic conditions. Stand structure is the physical and temporal distribution of trees and other plants in a stand. The distribution can be described by species; by vertical or horizontal spatial patterns; by size of living and/or dead plants or their parts, including the crown volume, leaf area, stem, stem cross section, and others; by plants ages; or by combinations of the above. Stand development is the part of stand dynamics concerned with changes in stand structure over time. Stand growth or productivity refers to changes in total volumes of all plants or parts of plants. Yield refers to the standing volume of all or parts of the plants at a given time. Site refers to an area's potential for tree growth; site usually incorporates an area's soil and climate conditions. (These definitions are modified from Ford-Robertson, 1971.) Disturbances are any relatively discrete events that disrupt the stand structure and/or change resource availability or the physical environment (Pickett and White, 1985). Both non-human and human-caused disturbances are considered, since tree response does not distinguish between non-human and human activities.

She flipped forward to Chapter 4. Disturbances and Stand Development and scrolled through Characteristics of Different Disturbance Agents: Fires, Winds, Floods, Erosion, Siltation, Landslides, Avalanches, Glaciers, Volcanic activities, Ice storms, Mammals, Insects and diseases. Tree Responses to Disturbances which included Trees surviving minor disturbances and Disturbances and regeneration mechanisms, followed by Applications to Management.

Why no mention of logging? she wondered as she flipped back to the Preface.

This book describes the various growth patterns of forests from a mechanistic point of view. Its purpose is to help silviculturists and forest managers understand and anticipate how forests grow and respond to intentional manipulations and natural disturbances. Demands on the forest have been increasing for timber production, wildlife habitat, water protection, recreation, and protection from fires, insects, and diseases. These demands have created an emphasis on prescribing site-specific treatments for individual stands of trees, rather than treating broad areas uniformly.

Ah, she thought, Management. The practice of forestry, silviculture, from which all human-desired values and products flow, from recreation to lumber.

She jotted thoughts into her notebook, looked up when she heard truck tires on gravel. It was Jackson’s pick up. He parked and strode up the hill. He toted sacks with apples, cheese, water, the two red and black plaid wool blankets from his truck, a canvas bag of tarps, stakes and ropes. He laid the items down and rigged a large tarp overhead. Grace helped. “Thanks,” he said. “It’ll get cold and wet soon.”

“I have questions,” she said.

“Shoot,” he replied, hammering a stake and pulling the guy line tight.

“The landscape is pretty stripped, but there’re some dead trees standing, here and there. Why?”

“Beetles,” he said. “A French study discovered 139 beetle species living on one old dead oak tree. 139! It’s an eco-system, a perfect nesting spot for small mammals and birds. So, the Forest Service selects a few dead trees—snags. But what with all the machinery and lines, snags can topple, kill a man—widow makers—so OSHA regs require us to clear ’em all out.” He sighed. “Conflicting agency regs, so a deal was struck where OSHA signs off on the logging plan as far as safety goes, pacifying our insurance broker, and we leave snags, making the Forest Service and the critters happy.” He shook the shelter, but it was solid. “That’ll hold,” he said.

They ate apples and watched the crew work. “Impressive operation,” said Grace.

“Rigs and pulleys, shackles and winches. Just big,” said Jackson.

“Where does your land end?”

He pointed to a ridge line and down to the valley. “We’ve logged here before I was born and the feds logged next door back during World War II. It’s far more efficient to log both sites at the same time so when we submitted a plan to log our side, we submitted one for their side too.”

“Looks like a moonscape,” she said.

“You’re not a Doug fir,” he laughed. “Doug fir are shade intolerant, need bare mineral soil to propagate—clear cut to you. Sun and rain on soil is the magic in the mix. Whether the clearing is made by logging, windfall, fire, or grazers, the trees don’t care. We try to mimic nature. When finished, we’ll give the area a prescribed burn to release nutrients into the soil, make it more receptive to new growth, and reduce debris that could fuel catastrophic fires years from now. When we’re done, it’ll be perfect for Doug fir propagation.”

He looked at her. “Come back next spring and see how fast trees grow here,” he said. “The land is so moist and fertile. Life and death and life again. Yeah, the life of individual trees are cut short, but the forest is being reborn. It’s a continuum, Grace.” He touched her shoulder and warned her, “If today’s image of trees being cut is the only image you take, it’ll be like attending funerals without ever seeing a baby born.”

She folded her arms, leaned back slightly. “If you got to make the rules, how would you log this area?’

He studied her body language. “Slower,” he said. “Definitely more fire. Natural regeneration. I’d want a landscape dotted with villages and small mills capable of handling different diameter logs for a diverse range of products.”

He turned to the cut and pointed to scattered stands of trees. “There,” he said. “And there. Legacy trees. We used LiDAR, light detection and ranging software, to find them, worked them into the plan. I like forester Derek Churchill’s description of these large, thick-barked fire-and-drought-resilient specimens. He calls them the ‘backbone’ of the forest. They offer a natural seed source for forest recovery after disturbance.”

“Lobsters,” said Grace. Jackson raised an eyebrow. “Lobsters,” she said, smiling. “Selecting for good genes.”

“Lobsters,” he said, laughing. “If I had my way, I’d like to see more irregularity in the cut, follow the lay of the land, instead of being so tied to the skyline.” He grinned. “Do more wetland and stream restoration work using beaver reintroductions; play around in the oaks down in the hilly areas. Fungi.” He laughed. “Make some money on truffles.”

“Why can’t you?” she asked.

Jackson laughed. “You assume I have control here! Government’s mandated bad policies and fire suppression for decades. They’re forcing us—while infrastructure is collapsing all around us—into a race against inevitable fire. They’re forcing us to compete against corporate tree plantations and slave labor-produced imports in a wide open global feudal market that they call free trade!”

He said, with bitterness, “It’s all rules ’n’ regs generated by treaties and laws written by people who’ve never set foot on this land, and are never held accountable.”

He thought to himself, They fly over, look down on cuts. ‘Mange on a dog’, they call it, laughing. Far too much contempt, too little understanding. Zero respect.

He stood and paced under the branches of the big Doug fir. “We are standing in the under-a-microscope, highly regulated and litigated Pacific Northwest. We have to make a livin’ in this highly competitive, pressurized, globalized techie environment and a lot of what I’d like to do, wouldn’t work business-wise, regulation-wise—it’s simply not possible here.”

He scowled. “Hence the shift to dense tree plantations with short harvest cycles of thirty years. Pencils out for shareholders.”

Grace sensed Jackson’s frustration, changed the subject. “What about that stream down there?” she asked.

“Federal fisheries biologists used to force us to clean out any litter that flew into streambeds.” He laughed. “Claimed anything impeding fish passage was bad. “My Dad made a darn good living cleaning out creeks. Then biologists decided woody material made for great fish habitat. Gives fish hiding spots, cools the water. Of course any fisherman can tell you fish love to hide under logs and in streamside undercuts so why’d it take biologists friggin’ forever to figure it out?”

He sat down. “The logging plan’s designed to minimize erosion. The soil’s porous here so we build culverts to funnel drainage to areas where absorption is high.” He pointed. “See there? Trees within a hundred feet of the stream are left standing. Streamside buffers can be too wide. We have some up here that are 300 feet wide in places. They cool the water to the point where insects disappear. No sun. Too cold.”

He sighed, shook his head. “For years, the biologists had zero science. Now they have too much, but it’s still just a snapshot in time. If you know what you’re looking at, you can read where it’s misleading, incorrect and, far too often, damned political. The Powers That Be fund what they want to match their agenda. Screw the truth.”

He pursed his lips, shook his head, continued, “In simplest terms, I live here, I grew up here. Everybody knows me. If I screw up, I’ll never hear the end of it from my neighbors who love to fish and hunt and care about this place. They catch me in the bar and give me a piece of their mind, especially the old folk—they have tons of time.”

Grace laughed. “The US is about 30% forested, right?” she asked.

“Yep,” he said. “Government owns the bulk of it. Half the saw timber, the timber used to make homes and buildings, is found on federal forests, most of it right here in the northwest, but actual production is about 80/20 private to government land.”

“Why should we trust the timber industry with its bad history?” she asked.

“What was done historically was basically legal and considered well within the existing social license of the times,” he explained. “Good and bad resulted. The experience generated lessons and those got incorporated into a new social license. That’s called progress in a democratic society. But when the social license gets fueled with misinformation, and the distribution of wealth from timber gets altered, the society as a whole suffers which is not the goal of democracy anywhere.” He shook his head. “Resource extraction is essential to our survival, yet it requires the Earth be disturbed. Urbanites overreact to any picture of trees being cut and scream global deforestation. They hate stumps and oil rigs, won’t watch a butcher or a miner work, but they drive happily in their shiny new Teslas to pick up soy burgers and fries, all wrapped up in paper. If you base your resource management policies on images chosen for shock value, a visual of a combine chewing up a bunny in a field of soybeans would freak out vegans, shut down the entire tofu industry!”

“But what about the destruction of the Amazon, the tropical rainforests?” she asked.

“Transfer the best stewardship practices for silvicultural systems to people everywhere and support good producers paying good wages with open trade. If we don’t, forests will be cleared for other reasons, palm oil production, even drug cultivation. We’re seeing it here. There are twenty grow farms within five miles of where we’re sittin’. It pays far better than logging.” He shook his head. “Support responsible foresters, I say.”

He stood and began pacing again. “You know, I’m really tired of the manipulation of moral outrage that says we only have two choices: global deforestation or preservation. That mindset is fueling a machine hell-bent on putting everyone out of business. I reject the ‘no use’ philosophy. We need lumber. We need paper. The issue is not will we cut trees, but how and where and who will cut trees.” He studied the sky, looked back at the job site. “I gotta go,” he said, walking away quickly.

Over the course of the afternoon, Jackson and Nate directed the crew. Jackson returned every hour or two to where Grace, protected from the steady drizzle by the little shelter, watched and learned, thought and wrote. Their conversations continued in broken threads.

“But with other parts of the US forested, must we log here in the last temperate rainforest in the US?” she asked Jackson. “Since we’re down to the last 10% of old growth, shouldn’t we save the ancient trees?”

Jackson grinned. “You’re just baiting me now, aren’t you?” She smiled. “OK, I’ll bite. Temperate forests are common,” he said. “Temperate rainforests, with over 55 inches of annual rainfall, not so much. Silvercreek gets 120 inches of rain a year and our rainforest gets a whopping 140 to 170 inches, that’s about 12 to 14 feet of rain a year! That doesn’t count all the water delivered to the trees via fog, cloud, mist and dew, the unmeasured occult water. I think harvest levels should take into consideration tree growth rates, which are higher in rainforests due to all that moisture.”

He thought, then said, “Too much rhetoric is designed to justify ‘not in my back yard’ policies. It says, we are so rich we don’t need to look at stumps anymore. Those forests in someone else’s backyard are not as important as our forests. All forests deserve good management, and good management includes logging. And fire. Many forests are so beautiful because we do use them.”

He studied the forest before him. “Pseudotsuga menziesii, Douglas fir. Not a fir at all—it’s an evergreen conifer species in the pine family, Pinaceae. Pseudotsuga means ‘false hemlock’. Doug fir is the most widespread of all Western trees with a range from central BC to Southern Mexico, 3,000 miles. Three varieties: Coastal, Rocky Mountain, Mexican. It grows in all but the wettest of soils, anywhere with a fire history.” He laughed. “I should probably repeat that—anywhere with a fire history.”

He patted the bark of the Doug fir under which they sat. “Take our friend Doug here, an impressive 200-footer who has withstood strong winds and tough times. I’ve read tree rings on this mountainside. They tell me Doug has survived drought, light burns and a massive fire 200 years ago. He doesn’t know it, but he’s growing half a mile from fed land where 80% of the trees are infected with bark beetle. He’ll get it soon, followed by root rot. In a short decade, maybe two, beetles will have eaten their way through his thick bark and he’ll burn or blow down. We could come back, but it’s unlikely we’d salvage much decent wood out of Doug then, as he decomposes into soil. It’s sensible to take Doug this month, along with his neighbors. We’ll clean up this entire area, do a light burn, protect adjacent areas from beetle infestation.”

He looked at Grace. “I’ll argue that logging is far more valuable to the human race than many jobs. Being a forester is a worthy and noble profession.” He sighed. “Yeah, we can ignore all this, let others make these decisions, let them do the sweaty labor. Are we so rich in the US that we can absorb the very high cost of mismanagement, while forcing our neighbors overseas to do the work of forestry, to live lives so real they draw blood?”

He took a breath. “The Olympics are near the mega city of Seattle and those people play and hike through these rainforests, blissfully unaware, never really seeing the forest for the trees. We can let Doug die, drop, decay, become soil. Choices. We can run freeways through millions of acres so tourists can drive around complaining about the smoke or the wet, snapping selfies sitting on Doug and his cousins who will all be lying on the ground or ash by year two hundred and fifty of their very long lives.”

He went quiet, surveyed the cut, the workers. “I’ve got to go, but let me add this. Nature has its own very special, very harsh way of managing forests. Add ten thousand dead and dying trees to this area, a million, and you have the makings of a very good bonfire. It’s wasteful but also a threat to our timber towns as well as campgrounds and hotels for eco-tourists, whatever they put in here.” He smiled, a tired smile. “Keep in mind, Grace, man is the only variable in the mix we can control. By directing his actions, you can make trees bigger or smaller, older or younger, the forest denser or less so. You can change the species, address disease, reduce fuel load. It’s gardening on the grandest scale. Whatever the management decisions made, long term, you’ll be needing loggers, even if some people don’t want to admit it.”

He looked to the deep green vista of trees, swaying in a breeze, as far as the eye could see. “Yes, you can let it all go, let nature do whatever nature wants. Stand back and watch. But when it all burns or blows down, don’t come running to me. If I can’t stay here, I’ll be in those other forests, the ones you told me you wanted cut instead of this one.” He shook his head. “This is my home. This is my life. I’ll make my stand here. At least I’ll give it my best damn shot.”

They said nothing for several minutes. The radio crackled. “Jack?” asked Nate. “A word on the plan?”

“On my way,” said Jackson.

<><><><>

The drizzle abated and the drone of chainsaws that had echoed from peak to peak went silent as the crew broke for lunch. Jackson returned, carrying a cooler and they ate lunch on a rock overlooking a fog-shrouded valley, the wool blankets wrapped over their shoulders.

“Where were we?” asked Jackson

“Choices,” she said. “But tell me about old growth, ancient trees.”

“What’s the definition?” he asked. “To which species are you referring? The Forest Service definition of old growth pegs the Pacific Northwest at about 30% old growth. The forests never were one solid block of old growth. They’re a mix of young, middle-aged, old, dying and dead trees. The ancient forest is a myth.”

He shook his head and said, “Beyond man’s take, logging, trees die naturally from fire, insects, disease, wind throw, or old age. It’s doubtful that our friend Doug here will make it to 1,000 or 1,300. You can put a fence around the old trees and say ‘hands off’ but they will still die. Think on it—if man harvests just the young trees while protecting the old ones, well, that’s a train wreck. It’s a long time coming, but you’ll collapse the forest.”

He went quiet for a minute, then continued, “In 1921, one third of all the timber on this Olympic Peninsula blew down. One third! We could have let those trees rot on the ground and imported our wood from someone else’s forest. It’s a decision that no one even considered in 1921. People used that salvaged timber to build San Francisco after the earthquake; built whole neighborhoods in Seattle and Portland, some beautiful and wonderful homes and buildings. As a utilitarian, I see beauty there, and a good dose of pride. A lot of those buildings are victims of bad economics, run down now, need patching and paint, even replacing. Ah, well.” He picked up some duff, let it blow in the wind.

“Wind is a frequent disturbance event on the Olympic. We had a big one in 1880 and the Big Blow in 1921 that felled two thousand square miles of timber. We had significant blow downs in 1934, ’62, ’79, ’81; a series in the 90s—1990, ’93, ’95, ’97. Don’t clean it up and insects will feast, summer will dry it. It will burn.”

He paused, then said, “The Sol Duc River Valley burned in 1308, 1508, 1701, 1895, 1907, 1951 and flared up in ’52, burned 35,000 acres in twelve hours, almost took out Silvercreek. Consider Paradise, Lahaina, other towns that ignored land stewardship. All land is managed, by man or by nature, in a cycle of death and mortality, fire, reality. Trees die, to be replaced by other trees in an endless cycle.”

A jay flew overhead and lectured them. Jackson looked up and it flew off. “Every tree,” he said, “in its turn, could become old growth, ancient, by anyone’s definition, but most won’t. I cannot guarantee a Doug fir forest if nature burns this fed land as intensely as it must, but if we manage it—log it, add fire—this landscape will return to healthy Douglas fir forest, a productive place to be admired and used long after you and I are gone.”

He studied the clouds crossing the sky, “One third of the world’s land base is forested and one third or more will be forested tens of thousands of years from now, if we make the right choices—and don’t get hit by an asteroid.”

He sighed. “There is a beauty in utility. There is a truth in reality.”

Grace pulled the wool blanket tighter over her shoulders. “Cradle to cradle.”

Jackson pulled the blanket down to cover her back. “In the simplest terms, the human population is not one solid block of similar people. It’s not possible or natural. No one would be dumb enough to insist we need to preserve more old people.” He laughed. “A preservationist campaign for ancient people! Put a fence around the old people, preserve them forever! Can’t be done. When it’s their time, they will leave this planet.”

He rubbed the stubble on his jawline and studied the sky again. “Hmmm,” he said.

Grace looked up, wondering what he’d seen. She saw cloud cover rolling in from the north and felt a bit of wind.

“We’re gonna want to get in the truck,” he said, picking up their things and heading to the shelter where Grace grabbed her things. She wondered what the weather was like in L.A. as thunder grumbled to the north. The sky flashed. Clouds quickly obscured the mountains and wind-whipped rain suddenly pelted the little shelter. She looked up at Doug. His smaller branches lashed wildly above but he did not budge.

Shit, she thought as they ran for the truck. Doug may love this, but I’m not built for 14 friggin’ feet of water a year!